It first occurred to the omniscient mind that he should

select on the banks of the aforesaid river some pleasant site, distinguished

by its genial climate, where he might found a splendid fort and delightful

edifices, agreeably to the promptings of his generous heart, through which

streams of water should be made to flow, and the terraces of which should

overlook the river.' Muhammad Tahir, Inayat Khan Shahjahan-nama, 1657-58.

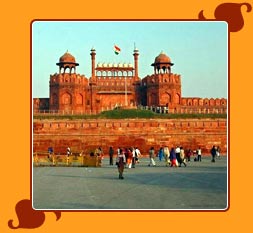

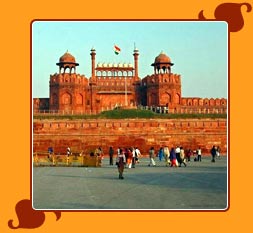

Such worthy thoughts, according to the royal librarian, prompted the Mughal

Emperor Shah Jahan to found a fresh city at Delhi in the mid-seventeenth

century. He called it Shahjahanabad, meaning City of Shah Jahan. At its

centre stood the Red Fort, a vast walled complex of beautiful palaces and

meeting halls from which the Emperor ruled with unmatched public pomp and

ceremony.

Today,

the surviving Fort buildings stand silently amid the still bustling city,

now called Old Delhi. The Red Fort's success was instant. It represented the

pinnacle of Mughal palace-fort building, and symbolized political and

economic power. It was also perhaps the most extravagant and sophisticated

theatre ever built for daily performances of one of the world's most

dazzlingly grand courts. But its glory was short-lived; as the Mughal Empire

waned, so did the Fort. Later Emperors abused the fine buildings, raiders

snatched its treasures, marauders wrecked its buildings and finally the

British, blind to its qualities, pulled down the greater part. Even this

century, what remains has been largely ignored, unappreciated and uncared

for.

But, despite the ravages of time and human action, the

extraordinary achievement of the Red Fort in plan and fine architecture is

still visible today, although it is unjustly ignored. It is time to set the

record straight, to look again at the surviving buildings and to bring the

Fort alive through the personality of its creator, Shah Jahan, and his

Court. The Red Fort and its surrounding city constitute the only large-scale

Mughal city planned and built from scratch to survive as a living city.

Built in just over nine years, it burst into life in 1648 and, although the

palace buildings are peopled only by ghosts, the city it supported still

thrives today and the inhabitants of its tiny lanes are often descendants of

merchants and craftsmen who served Shah Jahan and his Court, still

practising the same trades in the same areas.

Here they live and

work, shop in the markets and celebrate their festivals in the streets. And

a few old families who a generation ago deserted the lanes for spacious,

air-conditioned comfort in the New Delhi suburbs keep the family haveli

(courtyard mansion) in Old Delhi and speak proudly of the city they come

from, even if they have never slept a night in it. The key to the Red Fort's

success was firstly that it was designed not merely for Court pleasure. It

may have contained glittering palaces, but it was also the power-base for

the whole Empire, for internal government and external foreign affairs. It

was built for defence, too, although this role would later prove its

Achilles' Heel. The Red Fort was also a complete community, a

city-within-a-city, with its own bazaars (the covered Chatta Chowk is a

token survivor), gardens and mansions for favoured courtiers.

Every

detail of layout and every building reflected Mughal greatness, using the

finest materials to realise the most mature Mughal designs. Secondly, the

supporting city was an essential part of the original plan. It had its own

protective walls; its great mosque, the Jama Masjid (Friday Mosque), stands

on the only hillock so all can see it; and its host of specialist bazaars,

which supplied the vast Court with everything it needed from silk slippers

to fresh Kabul melons. The city gained enough momentum to survive, albeit

less glamorously, when the Mughal Empire waned and, more importantly, when

the British built New Delhi and its competing shopping centre at nearby

Connaught Place. Thirdly, the whole of Shahjahanabad, both Red Fort and

city, was a thoroughly royal undertaking.

The city outside the

Emperor's palace-fort was an extension of it in design, patronage and

function. Indeed, Fort and city sustained one another, living in symbiosis.

The Jama Masjid encapsulates the idea, for it was planned as the mosque for

both the city and the royal Red Fort, which had no internal place of prayer.

The city's main market street, Chandni Chowk, was laid out by one princess;

additional markets, sarais (inns), Hammams (baths), mosques and gardens were

given by other members of the royal family; and grand havelis (mansions)

were built by favoured princes and courtiers. The havelis have mostly gone,

but those markets and places of worship are still focuses of Old Delhi.

Conversely, the public had access to the daily public meetings held in the

Diwan-i-Am (Public Audience Hall) in the Fort itself, a fundamental element

of Mughal rule. As a royal undertaking, the Emperor's personal interest and

vast finances were behind the project.

With a stable empire and a

huge income from taxes paid by his subjects, Shah Jahan could indulge his

obsession, building a new and magnificent capital whose centrepiece would

become a legend in his lifetime and whose magnificent planning and buildings

would survive, in part, to be admired by posterity. Shah Jahan seems to have

taken an active part in the design, direction and encouragement of the whole

project. He was involved in the general plan and in the detailed designs for

the marble palaces, the Chatta Chowk, the Jama Masjid and probably more. As

one recorder noted, perhaps with an overdose of loyalty: 'Occasionally His

Majesty supervised the work of goldsmiths, jewellers and sculptors.

Thereupon specialists commissioned to design new buildings would submit

their plans to His Majesty, who discussed them with expert persons .

Various monuments, which even the best-versed architect could not have

devised, were drawn up by His Majesty personally. His advice or his

objections were regarded as binding.' Forthly, the Red Fort and its city are

an inspired triumph of urban planning. Within the Fort, the core of the

design is T-shaped, the cross-bar consisting of a string of palaces facing

the Yamuna's cool river breezes on the east side of the Fort. To the west,

they face the main axis of the Fort and city: a procession of increasingly

less private and less royal buildings which leads to a giant gateway, out of

the seat of power and into the city's principal thoroughfare, Chandni Chowk.

Finally, each building in the Red Fort displays the hallmark of perfect

taste and elegance.

Built at the height of one of the most

cultured courts the world has known, this is Mughal palace architecture at

its most ambitious and sophisticated. Imagined in its original completeness,

it would have easily outshone its contemporary European rival, Louis xiv's

palace at Versailles, and it covered twice the area of the largest European

palace, the Escorial. Of the surviving structures, each one perfectly

fulfils its function. At the same time, each is visually satisfying, relates

happily to its neighbours and fits snugly into the overall plan. Lines are

simple, proportions human in scale, detailing restrained and both materials

and workmanship of the highest quality. Architectural historian Percy Brown

judged it in 1942 as 'the last and finest of those great citadels,

representative of the Moslem power in India, the culmination of the

experience in building such imperial retreats which had been developing for

several centuries.' Thus the Red Fort symbolizes the apex of Mughal cultural

refinement